Photovoice is an approach mostly used in the field of education which combines photography with grassroots social action. Subjects are asked to represent their community or point of view by taking photographs. It is often used among marginalized people, and is planned to give insight into how they conceptualize their circumstances. As a form of community consultation, photo voice attempts to bring the perspectives of those “who lead lives that are different from those traditionally in control of the means for imaging the world” into the policy-making process. It is also a response to issues raised over the authorship of representation of communities.

Problem in Photovoice

It can be challenging for researchers to observe some of a community’s most important behaviors, particularly when that community is wary of outsiders, isolated, underserved, oppressed or operating without written language. In these situations, observational research conducted by outsiders can result in a skewed and imprecise view of the community, which can then result in a poor understanding of its needs, assets and cultural values. Furthermore, researchers entering a community who attempt action-oriented research or social change may have difficulty ensuring that the progress made in their presence will remain in effect or continue to develop upon their departure from the community. Without a powerful emotional picture of a community and its residents, policymakers may misrepresent or fail to consider many of its most important aspects when making relevant decisions.

Solution

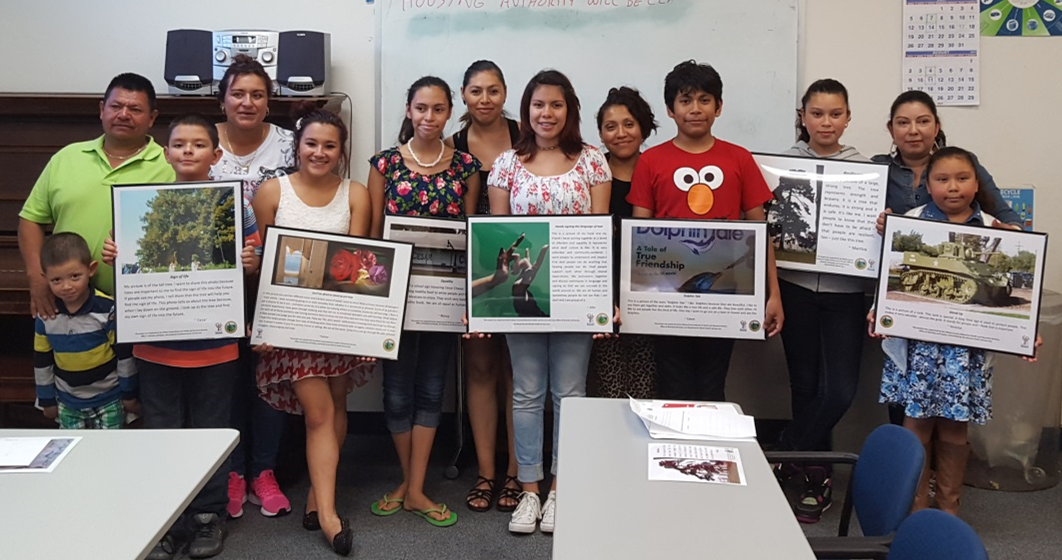

Photovoice, a participatory research methodology first formally articulated by Caroline Wang and Mary Anne Burris (1997), provides a process by which people can “identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique”. The method builds on a history of earlier participatory needs evaluation work in healthcare and social health education, on theoretical literature from the fields of feminist theory and documentary photography, and on a number of practical photographic traditions (Wang & Burris, 1997).

The method is based around the provision of cameras and associated physical and theoretical infrastructure to individual community members. These individuals are then prompted to capture visual representations of their everyday lives so that researchers working with the community might gain insight into previously invisible practices and assets, helping the community to better engage in critical dialogue around the problems and opportunities it faces.

Used When

This process is most helpful when used at the front-end of a project, as well as during the assessment and analysis stage to gauge success and validity.

Used For

Activity-focused research, needs assessment, problem-finding, problem-solving, solution implementation activity, project analysis and evaluation. Photovoice has been used successfully in projects related to issues as diverse as infectious disease, health education, homelessness, economic barriers, sexual domination, diasporas, population isolation and political violence (Catalani & Minkler, 2010).

Process

The following are the steps needed in conducting photovoice

1) Demographics – Clearly define the demographics and region of the community. Generate a list of partakers that is representative of the gender, age, occupational and economic diversity of that community. Consider other demographic criteria of particular relevance to the community if there are.

2) Budget – Make sure that there are enough funds for purchasing numerous cameras as much as the number of participant. Also consider the costs associated with taking the images, image development, transportation of equipment and a method by which photographers can communally examine each other’s work (a slide or data projector, for example).

3) Introduction – Gather the community representatives together, and explain to them in an easy and inclusive way why they have been chosen as representatives and how photovoice works as a research methodology.

Address any questions or concerns from the group, if possible. Once the group has agreed upon a mutual understanding of the research process and purpose, move forward with training.

4) Training – Teach the representatives on how to use the cameras provided to them. Include basic photographic concepts as well. Wang & Burris (1997) suggest minimizing the amount of time spent on specifically technical and aesthetic training, while research conducted by Catalani & Minkler (2010) suggests that prolonged and increasingly rich training exercises tend to produce more engaged participants in the long term. Discussions around photographic ethics and power dynamics should also be conducted before any shooting begins. Questions such as, “How is it acceptable to photograph a person?” and “Would you take someone’s picture without telling them?” are good starting points.

The first photographic task should expand participants’ knowledge of photographic principles while considering community cultural values in suggestions of subject matter and setting. Photographers should set out into their communities with open minds and a concentrate on capturing scenes that are related to their everyday lives. While the photographers should be encouraged to seek out important situations, they should also be encouraged to consider the mundane or obvious as relevant subject matter.

5) Viewing – Once the representatives are done with taking pictures, they should return the images to the facilitators. Facilitators should develop the images as promptly as possible, and return prints to the individual community representatives who shot the photographs. An additional set of each photographer’s images should be converted into a medium for communal viewing and reflection. Photographers may want to keep individual copies of their own photographs or give them to other members of the community, so it is important not to only produce a version made for communal viewing.

6) Discussion – Once the images are developed and the photographs are delivered, it is time for the discussion phase of the process. To begin this phase, ask each representative to choose a subset of their roll that they find particularly interesting or relevant for group discussion.

In a group meeting, the representatives will view each other’s work and are encouraged to tell a story about it. This is the contextualization part of the discussion phase.

7) Analysis – The representatives will the identify colors or themes that appear repeatedly. In Wang & Burris’s (1997) original work in the Yunnan province of China, for example, numerous photographs depicting water-related issues (e.g., a man stooping over a cistern, children climbing poles to replace electrical infrastructure for water purification, women boiling water in front of their homes) led to the realization that constructing clean water reserves in the community was more important and relevant than increasing access to written knowledge.

At this stage, the steps that facilitators and community members will take are more flexible and open to interpretation. If the project was intended as the lead-in to an action-oriented project, then these storytelling series and photographic records may be used to persuade policymakers and government officials of the significance of allowing the community to decide its own priorities. If the research was intended as a knowledge-acquisition activity for the community, then more time can be spent ensuring that community representatives have a sufficient understanding of the photovoice method and process to teach additional members of the community, or even members of other communities.

An important step to make sure that the project’s process and infrastructure support potential community-run activities in the future is to make the cameras and other equipment available to the community either free-of-charge or at a price appropriate to the community’s economic capability. The continued availability of equipment needed for photovoice activities offers significant benefits to the community in terms of action, advocacy, community values and individual empowerment, even after the project’s outside facilitators and researchers have departed.