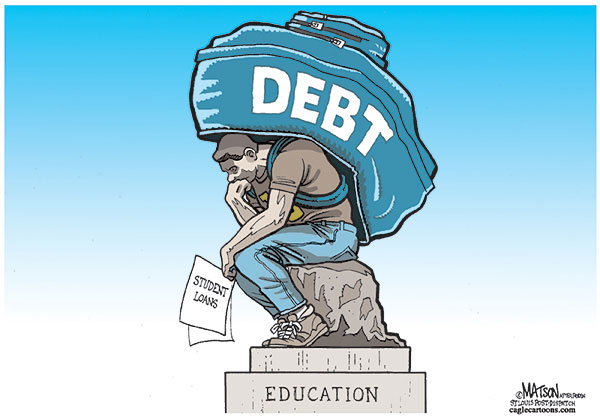

Apparently, higher education is becoming increasingly more and more expensive and it’s not getting results.

It doesn’t lead to graduates getting jobs that allow them to pay off the debts they’ve accumulated from that education.

That doesn’t mean that higher education should only be judged based on graduate salaries. Even if we consider a liberal arts education significant because it contributes to your critical thinking skills and makes you a better citizen, there are few things that needs to be considered:

- Skills are not being taught effectively.Take a look at the studies in the book Academically Adrift, which surveyed thousands of students before, during, and after attending college, tracking their learning and critical thinking abilities. The results were largely flat—higher education as it is now didn’t actually enhance skills. So forget about jobs and outcomes. Even the learning we’re claiming is valuable independent of those factors doesn’t actually seem to be happening in practice. College doesn’t seem to have the impact people want it to have in terms of that harder to articulate value and experience.

- Even if done effectively, this sort of education shouldn’t have such a high cost that it destroys your ability to pay off your debts. The purpose of higher education is nothing short of helping people build a better life. People can debate about the value of simply “being educated” and how that contributes to having a better life, but you can’t argue with the fact that being put into devastating debt without being able to pay it off makes your life much worse. It wasn’t always this way. People used to be able to have enough money for college by working summer jobs. But those days are long gone.

There are 2 main factors why people now cannot afford higher education:

- Unlimited access to student debt: that’s the giant elephant in the room. By creating a pool of unlimited capital without requiring transparency or accountability regarding outcomes, we’ve bred a lot of bad behavior. There are private equity companies entering the space, realizing they can earn more profits by enrolling tons of people for enormous fees. There are easily available student loans without checks and balances. It’s not dissimilar to what happened with the housing crisis—easily attainable capital corrupted by bad actors. You see it all over.

- Misconception about the value of a degree.As a country, we look at historical data about college performance and concluded that going college is a great idea for everyone. It is perceived that, based on this data, people with college degrees do better. Even today, this data holds. So we said let’s send everybody to college. It changed the whole culture of education. We started judging high schools and charter schools based on their ability to get people into college.

There’s a big reason this outlook is flawed: these institutions are built for a certain type of student—one who can afford it, one with a certain academic background. Now we’re saying, let’s shove every person into this system even if it wasn’t built for them. It’s like saying “Stanford grads seem to do well; let’s send everyone in the country to Stanford.” Obviously, that’s ridiculous.

Studies reveal that the students who often struggle the most from student loan debt tend to be low-income—people taking out smaller loans but later dropping out of college. They’re left without a degree that might help them get a job that’ll make them to pay back their debt and they have enormous interest rates on their loans.

Sadly, people from low-income backgrounds and under-resourced schools and give them scholarships to universities where they are surrounded by people who are generally well-off, who never really encounter difficulty, who are able to attend parties instead of working to support themselves. These students are thrown into a system not designed for them—without giving them the proper support infrastructure—and we expect them to do just as well the other students. Of course, it doesn’t work out like that.

Nevertheless, there are ways to handle these issues:

Long-term: Reform Title IV. This is a hard problem because it requires an act of Congress. Any reform you propose to Title IV (federal financial aid) makes it seem like you’re trying to make college less accessible and the lobbyists will pounce on that. But eventually, Title IV needs to be reformed to require much more transparency and accountability for the aid that’s given. Furthermore, there needs to be a shift so that people will know that one-size-fits-all education doesn’t work. Higher education doesn’t have to be a four-year degree; it can come in a lot of forms and people should be able to acquire an education based on who they are and what will be most valuable to them.

Medium-term: Accountability. Colleges can’t keep functioning for years and years taking students’ money without being liable for outcomes. Public companies have to have their data audited. The government is giving schools a lot of money and they should demand similar accountability: schools and accreditors that don’t meet certain outcomes should not be eligible to give student loans.

Short-term: Forced Transparency. Putting “Surgeon General”-style warning on student loan documents would make a great impact. Before any student signs a loan, they should have to read a giant disclaimer that states that they are about to enroll in X major at Y college and shows, for other students who have followed that course of study over the last five years:

- the percentage of enrolled students who graduated within six years

- the percentage currently in default of their student loans

- the average amount of student loan debt per graduate

Certainly full outcomes reporting would be preferred, but this is data that the government already has access to right now. So this could be enacted overnight.