Education economics or the economics of education is the study of economic issues relating to education, which also involves the demand for education and the financing and provision of education.

From early works on the relationship between schooling and labor market outcomes for individuals, the field of the education economics has grown rapidly to cover virtually all areas with connection to education. It has become a very vibrant area for research by young researchers, and it has led to four separate Handbook volumes covering both theoretical and empirical issues.

Demand for education

The dominant model of the demand for education is based on human capital theory. The main idea is that undertaking education is investment in the acquisition of skills and knowledge which will increase earnings, or provide long-term benefits such as an appreciation of literature (sometimes referred to as cultural capital). A rise in human capital can follow technological development as knowledgeable employees are in demand due to the need for their skills, whether it be in understanding the production process or in operating machines. Studies from 1958 tried to calculate the returns from additional schooling (the percent increase in income acquired through an additional year of schooling). Later results attempted to allow for various returns across persons or by level of education.

Statistics have revealed that countries with high enrollment/graduation rates have grown faster than countries without. The United States has been the world leader in educational advances, beginning with the high school movement (1910–1950). There also seems to be a correlation between gender differences in education with the level of growth; more progress is observed in countries which have an equal distribution of the percentage of women versus men who graduated from high school. When looking at correlations in the data, education seems to generate economic growth; however, it could be that we have this causality relationship backwards. For example, if education is seen as a luxury good, it may be that richer households are seeking out educational attainment as a status symbol, rather than the relationship of education leading to wealth.

Educational advance is not the only variable for economic growth, though, as it only explains about 14% of the average annual increase in labor productivity over the period 1915-2005. From lack of a more significant correlation between formal educational achievement and productivity growth, some economists see reason to think that in today’s world many skills and capabilities come by way of learning outside of tradition education, or outside of schooling altogether.

An alternative model of the demand for education, commonly referred to as screening, is based on the economic theory of signalling. The essential idea is that the successful completion of education is a signal of ability.

Financing and provision

In most countries school education is mainly financed and given by governments. Public funding and provision also plays a major role in higher education. Although there is wide agreement on the principle that education, at least at school level, should be financed mainly by governments, there is considerable debate over the desirable extent of public provision of education. Advocates of public education argue that universal public provision promotes equality of opportunity and social cohesion. Those who oppose public provision advocate alternatives such as vouchers.

Education production function

An education production function is an application of the economic concept of a production function to the field of education. It links various inputs affecting a student’s learning (schools, families, peers, neighborhoods, etc.) to measured outputs including subsequent labor market success, college attendance, graduation rates, and, most frequently, standardized test scores. The original study that prompted interest in the idea of education production functions was by a sociologist, James S. Coleman. The Coleman Report, published in 1966, concluded that the marginal effect of various school inputs on student achievement was small compared to the impact of families and friends.

The report introduced a large number of successive studies, increasingly involving economists, that provided inconsistent results about the impact of school resources on student performance. The interpretation of the different studies has been very controversial, in part because the findings have been directly entered into policy debates. Two isolated lines of study have been particularly widely debated. The overall question of whether added funds to schools are likely to produce higher achievement (the “money doesn’t matter” debate) has entered into legislative debates and court consideration of school finance systems. Additionally, policy discussions about reducing the class size heightened academic study of the relationship of class size and achievement.

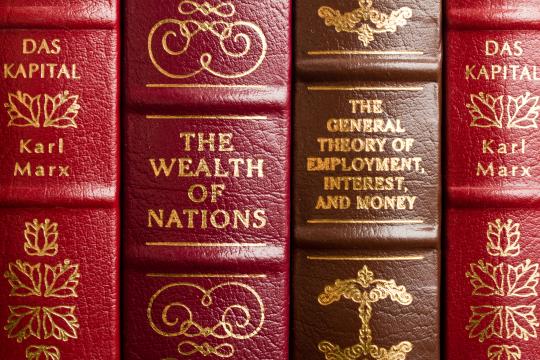

Marxist critique of education under capitalism

Although Marx and Engels did not write mostly about education the social roles of education, their concepts and methods are theorized and criticized by the influence of Marx as education being used in reproduction of capitalist societies. Marx and Engels approached scholarship as “revolutionary scholarship” where education should serve as propaganda for the struggle of the working class. The classical Marxian paradigm sees education as serving the interest of capital and is seeking alternative modes of education that would prepare students and citizens for more progressive socialist mode of social organizations. Marx and Engels understood education and free time as essential to developing free individuals and creating many-sided human beings, thus for them education should become a more important part of the life of people unlike capitalist society which is organized mainly around work and the production of commodities.